One of the things I find most delightful about history is that, while the people of the past wore funny clothes and sometimes thought about the world in a startlingly different way, many things remain the same. I like a drink, and it gives me warm and fluffy feelings to think that British people 200-ish years ago also liked a drink. Or several.

Like all aspects of Victorian culture, drinking was strictly segregated on class and gender lines, partly on account of the expense of booze, partly through custom and preference.

Working class boozers

Working class men and women partook of two beverages: beer and gin. Wines and other drinks were not widely available and were out of their price-range, as they were imported.

Beer has been brewed in Britain for centuries, and until recent times formed a vital part of the British diet. It really was a staple food. Water was unsafe to drink, especially in towns, giving people everything from an upset stomach to cholera. Since water could be deadly, everyone drank beer. This was brewed at home, by women, or in small breweries. Even as a commercial concern, brewing was traditionally one of the few professions open to women. Typical beer had a low alcohol content – maybe 2 percent – and was drunk all day long from breakfast to bed-time by men, women, children, babies, pregnant women, everyone. It was often thick and nourishing, filled with vitamins and minerals from the grains.

Typical boozers

By the Victorian era increasing gender divides and the growth of industrial breweries pushed female purveyors of craft beer out of the market. Since the working classes lived in such cramped conditions in towns and cities, they turned away from home brewing and towards industrially produced beer, served in pubs. Where town-dwellers drank at home, they usually sent a child off to the pub with a tankard to fill up. Bottled beer was not available until later.

This meant that all working class districts were crowded with pubs, and they provided a friendly home from home. Plenty of gas-light and roaring fires made them often much more comfortable than people’s miserable hovels, and many men could barely be prised away from the pub.

‘Behind the Bar’ by John Henry Henshall

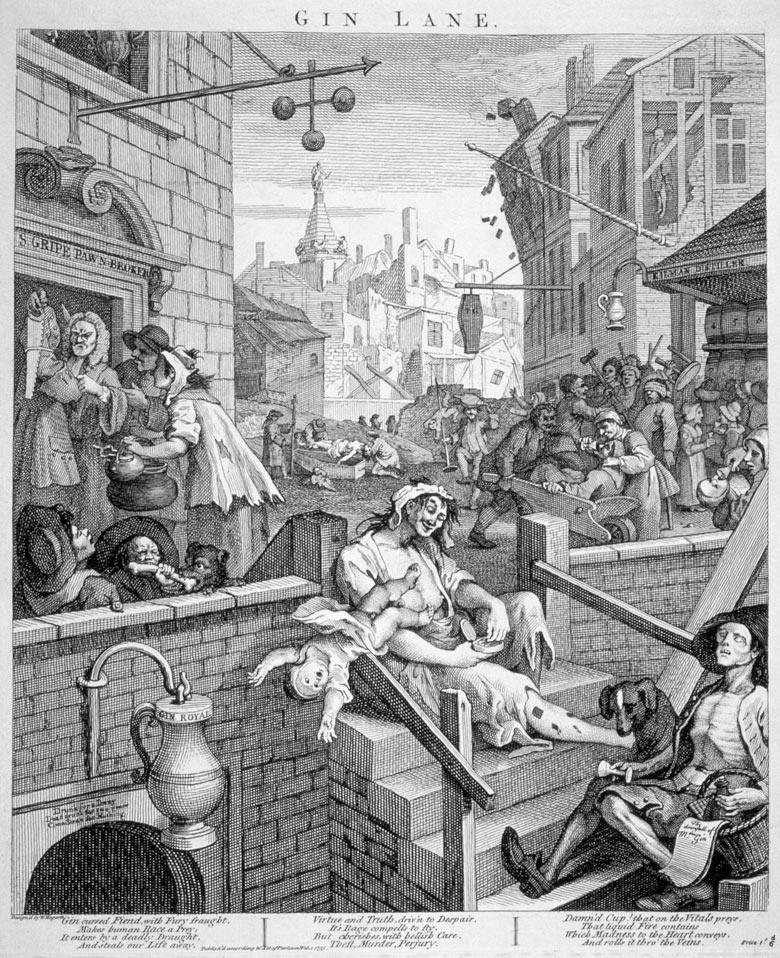

Gin was first produced in Britain after the Dutch King William of Orange took the throne in 1688. Years of excellent harvests had left Britain with a grain surplus and low prices. He took advantage of this by reducing taxation on distilling. The following year, British distillers produced around 500,000 gallons of neutral grain spirit. Now gin is in fact just neutral spirit – vodka – flavoured with juniper and anything else that takes the distillers fancy. The British flavoured their alcohol with juniper in honour of their King’s favourite Dutch drink, Jenever. And that’s how gin was born. By the 1720s London’s distillers produced 20 million gallons of spirits a year, as well as a staggering amount of illegal moonshine. In the mid-century around 1 in 4 London houses contained a working gin still, pumping out high-strength booze. Hogarth’s etching ‘Gin Line’, portraying the horrors of a city in the grip of an epidemic of alcoholism, wasn’t much of an exaggeration. Gin was called ‘mother’s ruin’ for a reason.

Hogarth’s ‘Gin Lane’

The gin craze had died down by the nineteenth century, but it was still the widely available alternative to beer. Drunk neat or with a bit of sugar, it was still popular with working-class women in need of something fortifying. As there was little refrigeration and water was still unsafe, there was no ice for the working classes. Gin was drunk at room temperature, or warm.

But working class drinking culture came under threat during the nineteenth century from the temperance and teetotal movements. Temperance – moderation in drinking – was advocated by middle class philanthropists and evangelical Christians, while the teetotal movement was largely led by the working classes themselves. There was probably some truth in their assertions that drunkenness led to poverty, deprivation and domestic violence, especially for the women and children who bore the brunt of a man’s drinking. But on the other hand, the middle classes simply feared and hated mobs, rowdy and uncouth behaviour, and people making a public spectacle of themselves. They were trying to impose middle class values on people who were unlikely to gain any material benefit from adopting those codes of behaviour. Unfortunately, temperance also had side-effects. When people swapped nourishing Victorian beer for plain old water, levels of malnourishment and disease went up. Drinking plenty of beer was actually surprisingly good for you.

A poster for the temperance movement

Well, that’s told ’em!

Middle class tipplers

The respectable middle classes rarely went to pubs. Men might have gone to a gentlemen’s club though. Here they could eat, drink, meet for business or a chat with friends, and read the newspapers and periodicals. The middle classes stuck to wine, fortified wines like sherry and port, possibly a little brandy.

But the century brought an exciting new trend in drinking: mixed drinks. British people had long been used to spiced, sweetened, fortified punches, often served hot – think of mulled wine or mulled cider. But mixed drinks were an American novelty. Charles Dickens was one of the first to write about them, in his American Notes for General Circulation. Dickens visited America in 1842 and in Boston he gleefully partook of an array of newfangled mixed drinks, with strange names like “the Gin-sling, Cocktail, Sangaree, Mint Julep, Sherry-cobbler, Timber Doodle, and other rare drinks.”

The “Cock Tail” was a mixture of strong alcohol, such as American rye whiskey, mixed with sugar syrup, water, bitters and nutmeg. Sangaree is essentially Sangria, the mint julep is still drunk today and contains whiskey, sugar, mint and water, and the sherry-cobbler is sherry, sugar and citrus with ice. The timber-doodle is anyone’s guess, though I desperately want one, whatever it is, just for the incredible name. Poor timber-doodle! Doomed to remain one of history’s unsolved mysteries.

The sherry cobbler, as featured in the Savoy cocktail recipe book

Dickens features the sherry cobbler in his novel The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit (1843-44). “Martin took the glass with an astonished look; applied his lips to the reed; and cast up his eyes once in ecstasy. He paused no more until the goblet was drained to the last drop. ‘This wonderful invention, sir,’ said Mark, tenderly patting the empty glass, ‘is called a cobbler. Sherry Cobbler when you name it long; cobbler, when you name it short.’” The most astonishing thing about it was apparently the drinking straw: they were pretty much unknown until then, and the sherry cobbler helped to popularise them. The Victorians were nothing if not lovers of novelty.

Notable Victorian drinker Charles Dickens

If you want to try a sherry cobbler at home, here’s a modern version of the recipe:

Muddle (that means squish up with a wooden stick) 3 slices orange and 1 tablespoon of sugar in a cocktail shaker; add 100ml of dry sherry and ice; shake until the outside of the shaker is cold and frosty; strain into a collins (tall) glass of crushed ice; garnish with an orange wheel and fresh fruit. For variety you can use any combination of citrus fruit, and you could add berries before muddling, or a little mint. You could also try adding a splash of a fruit liqueur.

A fancy, sexed-up modern version of the sherry cobbler

Mixed drinks were mainly drunk in American bars, for instance at the Savoy hotel, that catered for American expatriates. Gentlemen’s clubs and officer’s messes might also offer these kinds of drinks, and sometimes they were even drunk at home, though usually at large social gatherings.

The Victorians gained inspiration from How to Mix Drinks; or, the Bon-Vivants Companion by Prof. Jerry Thomas, published in 1862. Thomas’ book is a classic, featuring all sorts of punches, and well-known drinks like the Tom Collins, sours and flips. His signature drink was ‘the blue blazer’, which involved setting fire to whiskey and then pouring it, flaming, between different glasses. Better than Tom Cruise in Cocktail, eh?

Jerry Thomas’ classic guide

Jerry Thomas in action, with his ‘blue blazer’

Having said that gin was a rough and ready drink for masses, associated with alcoholism and working class debauchery, new gin-making methods actually led to its revival. Gin was no longer a rough, sweet drink, but was distilled in a new style, christened ‘London dry’. This rehabilitated the drink and gave it a new respectability. The gin and tonic originated in this era. Tonic water is made with quinine, which helps to ward off malaria. The drink was therefore very popular amongst the military and British colonialists in hot countries, especially India.

Indeed, gin became so respectable that recipes for gin-based drinks even appeared in Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management. The ingredients for a gin sling were listed as gin, 2 slices of lemon, 3 lumps of sugar, and iced water.

Upper class quaffers

No grand dinner would be complete without it’s accompanying alcoholic beverages. Fancy dinners reached the height of ludicrousness in the late Victorian and early Edwardian period, only to come crashing back down with the start of the First World War. In the meantime, dinner parties could have as many as 12 courses. Each course was accompanied by a different type of alcohol. White wine with fish and light dishes, red wine with meat, and Madeira, sherry or sweet wine with desserts. Champagne was often served following an entree.

The earliest British recipe book for mixed drinks is William Terrington’s Cooling Cups and Dainty Drinks from 1869. Teddington’s recipes are mostly for what we would think of as punches, based on wine and sherry, mixed with herbs, fruit, spices, etc. Rather like an endless parade of different types of Pimms, and obviously all intended for large groups. Teddington mentions that these cups and punches are very popular at Inns of Court and the City Guilds: all-male gatherings, where everyone got sloshed, but with fancy drinks, using fancy cups, and with lots of toasts and ceremonial nonsense. That made the whole business of getting off you face terribly classy, you see.

A fancy silver punch bowl, the kind used at posh Victorian parties

Here’s a summary of one of his recipes for ‘claret cup a la Brunow, for a party of twenty':

Place a large bowl into a larger bowl full of ice and water to keep it cool, then mix:

lemon balm; borage; slices of cucumber; 1 pint sherry; 1/2 pint brandy; lemon peel; juice of 1 lemon and 3 oranges; 1/2 pint curaco; 1 gill ratafia of raspberries; 2 bottles German; seltzer water; 3 bottles soda; 3 bottles claret; sweeten to taste

Personally I think this sounds rather disgusting, and I won’t be wasting any wine on attempting this or any similar recipes!

Ladies who liquid lunch

Middle class and upper class ladies certainly couldn’t get drunk. They also couldn’t really go anywhere without a man, except each other’s houses or an alcohol-free tea shop. So they stuck to tippling at home. They might have drunk wine with meals, and had the odd glass of ladies’ favourites champagne and sloe gin, but they had to be careful to never appear sloshed – that was very vulgar, regrettable behaviour for the working classes only.